Albert George, founder of the Resilience Initiative for Coastal Education. Photo by Dr. Shaleen Miller.

By Olivia Raines

On Jan. 30, I had the chance to hear from founder of the Resilience Initiative for Coastal Education (RICE), Albert George. George came to speak to students across various disciplines enrolled in the Natural Hazards Resilience Speaker Series, and share his experience performing on-the-ground participatory research to address natural hazard mitigation in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. His primary focus is in the Gullah Geechee Corridor, a stretch of coastal areas and islands along the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, primarily comprised of West African descendants from the transatlantic slave trade.

The Speakers Series brings experts to UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus to speak to Natural Hazards Resilience certificate students annually during the spring semester.

George spoke to the intersection of race and natural hazards mitigation, and is providing technical support through RICE to advocate for communities such as the Gullah Geechee that are typically left out of conversations around climate change and hazard mitigation. This is becoming increasingly critical, he said, as the low-lying coastal communities of South Carolina are facing imminent sea level rise in the coming years, and currently suffer persistent flooding due to rising ground water levels. George said that it is anticipated that Charleston, S.C., could be experiencing 180 days of flooding per year in the coming decades. He has been working within the Gullah Geechee Corridor for years, and is primarily focused on providing the Gullah Geechee community with access the technology and tools that they can use to, as he put it, “Hold their own flame.”

One of the most impactful moments of the lecture was when George showed that understanding the historical roots of the Gullah Geechee community was hugely important in contextualizing hazard mitigation strategies going forward. He explained that during the slave trade, West Africans were specifically brought to the States into slavery because they had intimate knowledge of large-scale rice production. Those individuals were responsible for the intricate technologies of rice production in the Lowcountry, and former rice plantations are now home to some of the world’s most popular wetlands for birding. In other words, the infrastructure they put in place is still used today. Understanding this historical context, George said, tells him that the descendants of today’s Gullah Geechee community were “large-scale waterland engineers.”

The spelling of RICE is not only a purposeful homage to this history, but also a vision-setting framework going forward. In his mind, if the Gullah Geechee community was able to perform engineering on a grand scale for rice production, those same principles can apply to today’s challenge of meeting the threat of sea level rise in coastal South Carolina.

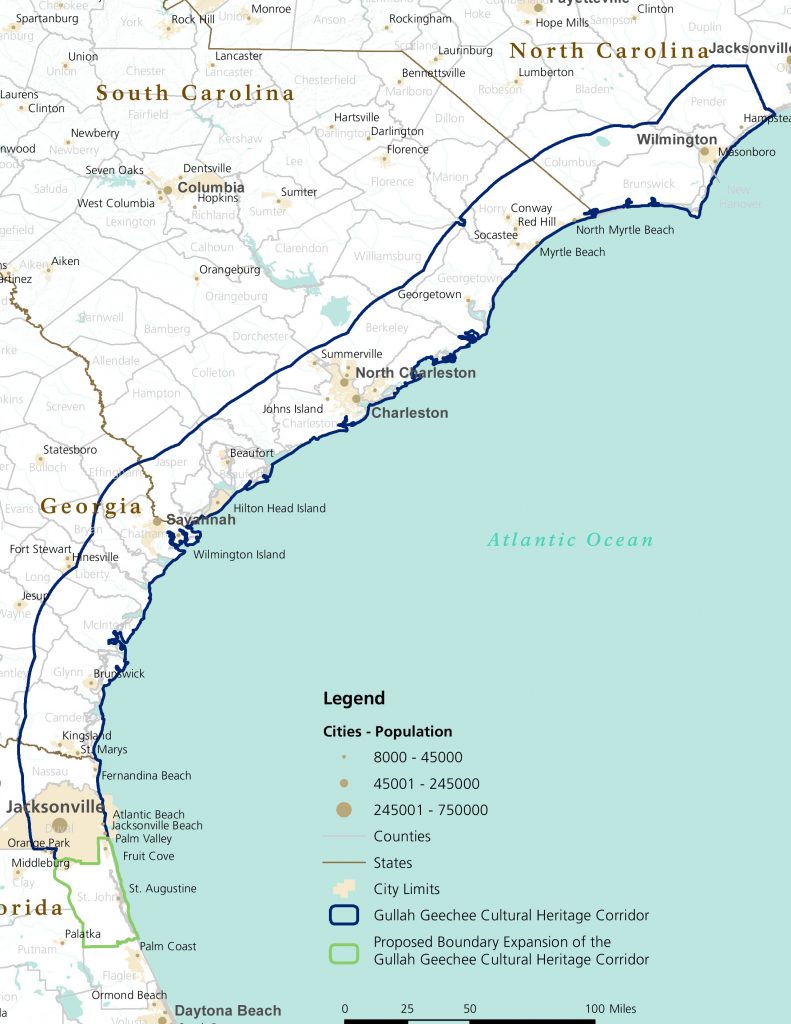

The Gullah Geechee Corridor extends 425 miles along the Atlantic Coast and 30 miles inland from the northern border of Pender County, North Carolina, through South Carolina and Georgia to the southern boundary of St. Johns County, Florida. The Corridor encompassess all or part of 27 counties. Image from the National Park Service.

RICE is now providing the technology to empower the Gullah Geechee community to do just that. For example, the communities he is working within have been introduced to a data source called Anecdata, where residents can take a picture of flooding, marsh die-off or other natural hazards in their area, and submit them to the Anecdata website. That picture will automatically be geo-referenced with National Oceanic and Atmoshperic Administration (NOAA) satellite data that others can view to learn more about the incident.

The use of this resource by community members has led to environmental experts coming to specific sites and committing funds to research, which his hugely transformative. Additionally, through his work as Director of Conservation for the South Carolina Aquarium, George has worked to create a free, user-friendly data source, SeaRise, which allows users to visualize the impacts of sea level rise at varying degrees on sea turtle nesting sites, elderly and vulnerable human populations, critical facilities and evacuation routes. The site is equipped with a tutorial and learning resources that help users interact with the map and understand the multidimensional effects of this imminent natural hazard.

One of George’s ultimate goals is that the knowledge being built through his current work will continue to translate into action. He hopes that other members of the communities he is working with to prepare for hazard mitigation will use the technical knowledge they now have to educate and advocate for those within and outside their own community.

Raines is a first-year master’s degree candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning, specializing in Housing and Community Development. She is primarily interested in the intersection of affordable housing and historic preservation, as well as rural and small-town economic development. She served as a community coordinator for Community Housing Partners, a non-profit centered around affordable homeownership and rental communities. Raines obtained her bachelor’s degree in Global Development Studies at the University of Virginia.