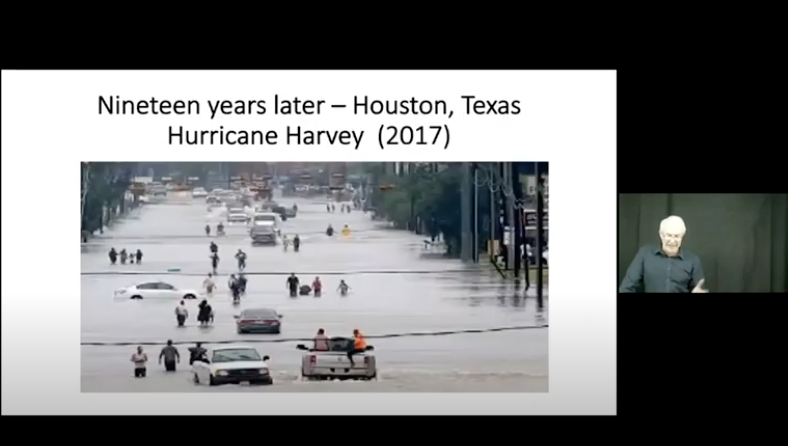

Donald Hornstein presents on flood insurance as part of the Natural Hazards Resilience Speakers Series in February.

By Rachael Wolff

“Flooding is head and shoulders above any other catastrophe that you or the world is going to face in its lifetime… in terms of sheer dollars and cents, especially with sea level rise.”

Rachael Wolff

Take it from Don Hornstein, who knows a thing or two about flooding. Prof. Hornstein holds the distinction of Aubrey L. Brooks Professor of Law at UNC-Chapel Hill and membership with the University’s Institute for the Environment, Ecology and Energy Program in the College of Arts and Sciences. He serves as a longstanding appointee on the Board of Directors for the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association. His current projects include writing about The Political Economy of Resilience and training lawyers to represent low-wealth communities in flood zone property buyouts.

Donald Hornstein

Prof. Hornstein took time out of his busy schedule on Feb.17, 2021, to participate in the Natural Hazards Resilience Speaker Series, a partnership between UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of City and Regional Planning and UNC’s Department of Homeland Security Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence.

Prof. Hornstein was a delightful speaker – candid, knowledgeable and enthusiastic. His presentation brought up many questions on the role of flood insurance, who it serves, and how the public should respond. Personally, this discussion resulted in three key takeaways: 1) Flooding is ubiquitous and expensive; 2) Disaster costs are political; and 3) Flood insurance should be accountable to the people.

Flooding is ubiquitous and expensive

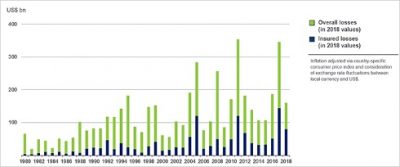

North Carolinians continue to face flood-related hazards: powerful and frequent hurricanes, sea level rise, riverine flooding, and nuisance (“blue sky”) flooding. This is also true globally, as Prof. Hornstein attributed 85 percent of worldwide insurance losses to flood. Yet, the total damage is often greater due to an insurance gap. He used the below chart to illustrate that, at most, one-third of all flood losses were covered by insurance between 1980–2018. This results in skyrocketing disaster costs and massive debt. In the U.S., this burden falls on the main supplier of flood insurance: Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Source: © 2019 Munich Re, Geo Risks Research, NatCatSERVICE as of March 2019 (https://www.iii.org/graph-archive/96425).

To try to encourage participation, the NFIP has historically offered artificially low rates that do not reflect a property’s actuarial flood risk. This subsidization has fostered a “safe development paradox”–building within the floodplain – as well as an overall “moral hazard” – people do not assume full risk of an action or decision. Severe Repetitive Loss Properties, often grandfathered into PreFIRM (Flood Insurance Rate Maps) rates, constitute only 1 percent of NFIP properties but make up 25-30 percent of claims. If it were not for flood insurance, Prof. Hornstein said, then most of the houses on the Outer Banks would not exist.

Disaster costs are political

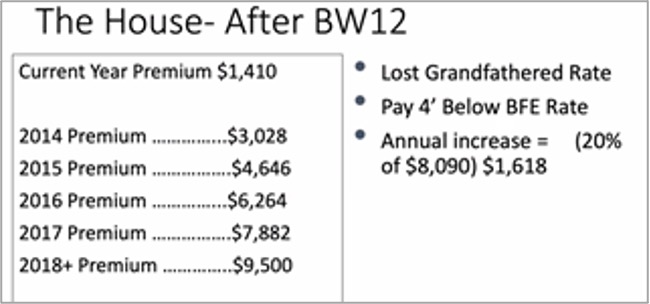

Prof. Hornstein noted that the solvency of the NFIP is on a collision course with social security, and this tradeoff would cost trillions of dollars. In order to improve the NFIP, FEMA needs to increase its rates. However, this has not always boded well with the public. The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 resulted in a loss of pre-FIRM rates, loss of grandfathered rates, and 25% annual rate increases until meeting the actuarial estimate. Prof. Hornstein illustrated that a grandfathered coastal property in 2013 valued at $900,000 paying $1,410/year would see an initial increase of $1,600:

Hypothetical example courtesy of Prof. Hornstein.

Such hikes resulted in grassroots resistance, especially since 40-45 percent of Americans live in a coastal zip code (i.e., flood zone). Prof. Hornstein explained the turbulence around Stop FEMA Now and Florida’s 13th congressional district special election in 2014, which were two of many movements that ultimately lead to the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014, repealing and modifying Biggert-Waters.

Flood insurance should be accountable to the people

This spring 2021, flood insurance premiums may rise again under FEMA’s Risk Rating 2.0, an updated rating structure complete with modernized FIRMs. While these hikes have equity implications – people who never had to buy flood insurance before could be designated in a special flood hazard area, and some people with lower rates could see their premiums increase up to 18 percent – Prof. Hornstein predicts that “resiliency may have its day.” With rates that reflect the costs of actual risk, actors may be incentivized to change behaviors in order to receive discounted premiums. The NFIP’s Community Rating System Program helps communities reduce flood insurance premiums by up to 45 percent if they undertake mitigation activities such as open space preservation, stormwater management, flood protection and acquisition and relocation.

Thus, the CRS lever is very important, and the main reason Prof. Hornstein supports public flood insurance. Local land use and hazard mitigation plans are requirements under the NFIP. Stronger land use controls and flood protections may guard against development in flood zones and save municipal costs.

Future action in this space requires asking the hard questions: Why are people located where they are? How can private development support public goals? How is flood insurance marketed, and how do people perceive risk? Answering all of these questions may require systemic change in how we support historically marginalized communities most vulnerable to hazards, as well as analyzing cost-share requirements for FEMA assistance.

Rachael Wolff is a second-year Master’s Candidate in City and Regional Planning focusing on Land Use and Environmental Planning and pursuing the Natural Hazards Resilient Certificate. She is interested in equitable disaster recovery, sustainable community and economic development, and historic preservation as revitalization. Previously, Ms. Wolff worked in federal emergency management and served a year with AmeriCorps NCCC FEMA Corps. She earned her undergraduate degree in International Studies at American University.