Donald Hornstein presents on flood insurance as part of the Natural Hazards Resilience Speakers Series in February.

By Rachael Wolff

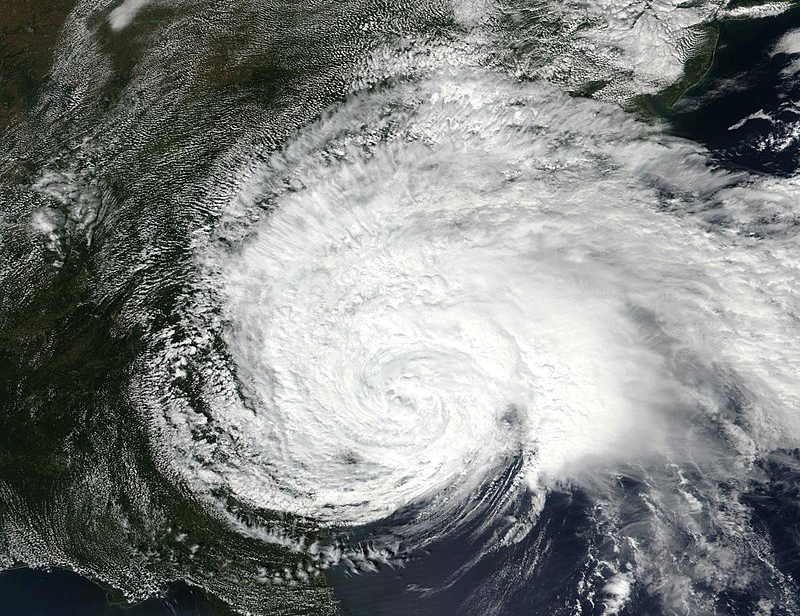

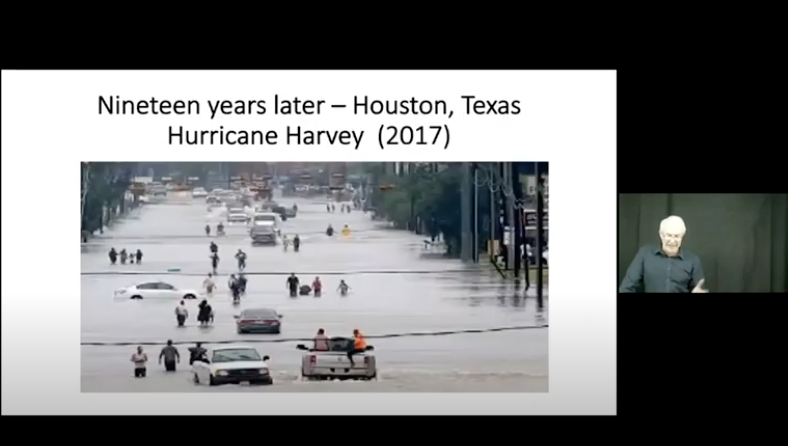

“Flooding is head and shoulders above any other catastrophe that you or the world is going to face in its lifetime… in terms of sheer dollars and cents, especially with sea level rise.”

Rachael Wolff

Take it from Don Hornstein, who knows a thing or two about flooding. Prof. Hornstein holds the distinction of Aubrey L. Brooks Professor of Law at UNC-Chapel Hill and membership with the University’s Institute for the Environment, Ecology and Energy Program in the College of Arts and Sciences. He serves as a longstanding appointee on the Board of Directors for the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association. His current projects include writing about The Political Economy of Resilience and training lawyers to represent low-wealth communities in flood zone property buyouts.

Donald Hornstein

Prof. Hornstein took time out of his busy schedule on Feb.17, 2021, to participate in the Natural Hazards Resilience Speaker Series, a partnership between UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of City and Regional Planning and UNC’s Department of Homeland Security Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence.

Prof. Hornstein was a delightful speaker – candid, knowledgeable and enthusiastic. His presentation brought up many questions on the role of flood insurance, who it serves, and how the public should respond. Personally, this discussion resulted in three key takeaways: 1) Flooding is ubiquitous and expensive; 2) Disaster costs are political; and 3) Flood insurance should be accountable to the people.