By Jaimie Hicks Masterson, Texas A&M University

Jaimie Hicks Masterson is Program Manager for Texas Target Communities at Texas A&M University and a researcher on the Coastal Resilience Center project “Local Planning Networks and Neighborhood Vulnerability Indicators,” led by Principal Investigator Dr. Phil Berke.

The City of Norfolk (Va.), one of two pilot communities working with researchers from a Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence (CRC) project, has begun formally adopting the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard at the center of the project.

Project researchers been working with Norfolk for a year to validate and test the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard. There are two reasons Norfolk conducted the evaluation: Their exposure and their leadership.

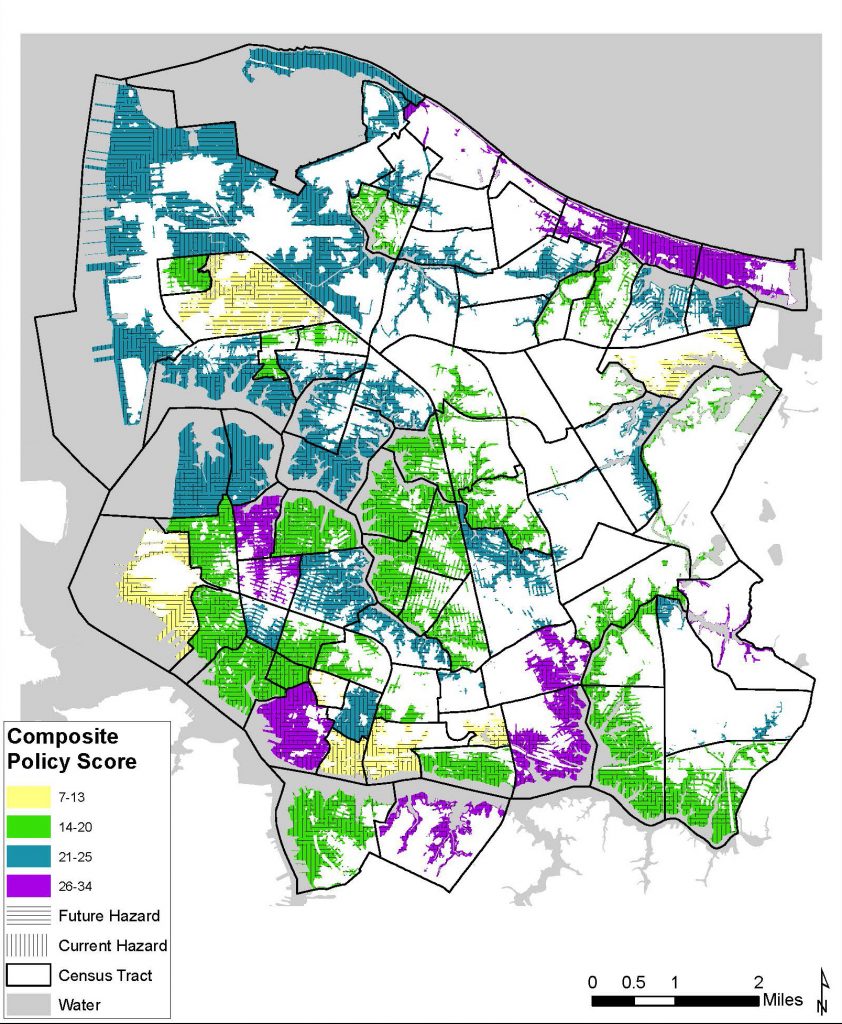

Composite policy scores for Norfolk, Va., based on the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard developed through a project led by Coastal Resilience Center PI Dr. Phil Berke.

Norfolk is located along a peninsula along the east coast of the state, an area known as the Hampton Roads region or Tidewater area. Norfolk has 144 miles of shoreline. Since 1972, they’ve had several federal disaster declarations including, two tropical storms and four hurricanes. Since 1927, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has recorded sea level, and Norfolk has experienced 15 inches of sea level rise since that time, the largest recorded on the East Coast. In fact, all census tracts will be affected in some way due to sea level rise by 2100. Today they have regular high-tide flooding.

It’s not just about exposure, but the people and places vulnerable to that exposure. There are 243,000 people in Norfolk at 4,500 people per square mile, a relatively high density. There are 120,000 civilian jobs, the world’s largest naval base and one of the country’s largest ports, the Port of Virginia.

The city council and mayor want to be a “leader in sea level rise” and they have a planning director thinking of innovative solutions. The Commonwealth of Virginia applied for and won the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s National Disaster Resiliency Competition, receiving $120 million. They work closely with the areas’ military bases, and are currently developing a plan for working with the cities in the region. Norfolk was one of the first Rockefeller Foundation 100 Resilient Cities. Because of that, they hired resilience coordinators and developed the Vision 2100 document, with a significant community engagement effort identified areas in the community that are vulnerable (see map).

These are the circumstances they find themselves in, but there are still more challenges. We continue to see three large problems which cities face:

1) Cities have a “plethora of plans problem” – they are swimming in plans. A catalyst of the project was when the research team looked at plans in Highlands, N.J., (with roughly 5,000 residents). Their hazard mitigation plan called for acquisitions and buyouts in an area along the coast. In the very same location, the comprehensive plan set goals and policies for economic development and mixed-use developments. Even communities with 10,000 people have at least four plans. When we see larger cities like Norfolk with 17 plans, it is unlikely to see a coordinated effort, particularly toward resilience.

2) Cities often have no collaborative process to understand how the various policies within plans are pulling in different directions.

3) Cities usually have no spatial understanding of how policies effect areas of a community, let alone their effect on hazard resilience.

In observing the pilot communities, the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard facilitates:

- Insight on the impacts of policies in regards to flood resilience. For example, a policy within a plan might say, “Encourage higher-density multifamily development in pedestrian-oriented urban areas with access to transit, a broad range of services and amenities and access to employment.” While this is a policy that many planners strive for, if it is in a flood hazard zone, unfortunately, it is actively increasing vulnerabilities. In Norfolk, they had not done such a comprehensive evaluation of policies. It was also an opportunity to see how different plans stacked up.

- Insight on the spatiality of policies and the impacts on specific areas. For example, a policy within a plan might say, “Strengthen controls on development within flood-prone and wetland areas by improving existing ordinances.” We can map the flood-prone and wetland areas, and most policies are inherently spatial. Because of this, we can see the stack of policies in a planning district. Norfolk hadn’t thought spatially about their policies before and were very excited to try the Scorecard, especially because of how spatial their Vision 2100 planning document, which identifies areas within the community to investment structural mitigation, areas to retreat, and areas for more dense development.

From right, Dr. Phil Berke, Jaimie Masterson, Stephen Cauffman and Joel Max discuss “A Guidebook + A Scorecard = An Integrative Framework for Community Resilience” at the Natural Hazards Workshop in Boulder, Colo., in July. Photo by Dr. Walter Peacock.

To reveal incongruities among community plans, the score itself is important. It allows you to map and visualize incongruities, but the real value of the scorecard comes from the conversations had during the process. Whether scores are positive, negative or neutral, cities are able to have better conversations, make better decisions and therefore better investments. This collaborative process allows cities to become self-aware regarding their overall network of plans and the integration of the policies for a particular district.

Within Norfolk, despite very good scores, the tool revealed weaknesses and inconsistencies throughout the plans. For example, the location criteria for community facilities within the comprehensive plan did not include factoring resiliency metrics, but instead only focused on accessibility to populations and other public uses. Additionally, Norfolk planning staff indicated they had not previously evaluated the hazard mitigation plan and the Scorecard provided a methodical tool. Now they are making a variety of “text amendments to better incorporate the actions aimed at mitigation and resilience as outlined” in the hazard mitigation plan across other planning documents. The report said that Norfolk’s actions were “far too one-dimensional with little specificity or policy implementation tools identified,” particularly within the hazard mitigation plan that did not specify which “appropriate strategies to mitigate the impact of flooding to existing flood-prone structures.” Finally, the Scorecard revealed the quantity of policies focused on vulnerability by district. The city stated they see now that they should include additional policies for other vulnerable planning districts.

Going forward, the research team will develop physical vulnerability and social vulnerability maps as a way to offer additional insight for targeting “hotspots” within the community.